- Login

Critical Spatial Practice

‘Originally (at least in English) translation was about the biggest difference of all: that between being alive and being dead.’ Susan Sontag, ‘On Being Translated’, in Where the Stress Falls (London: Penguin Books, 2001), pp. 334–47, p. 339.

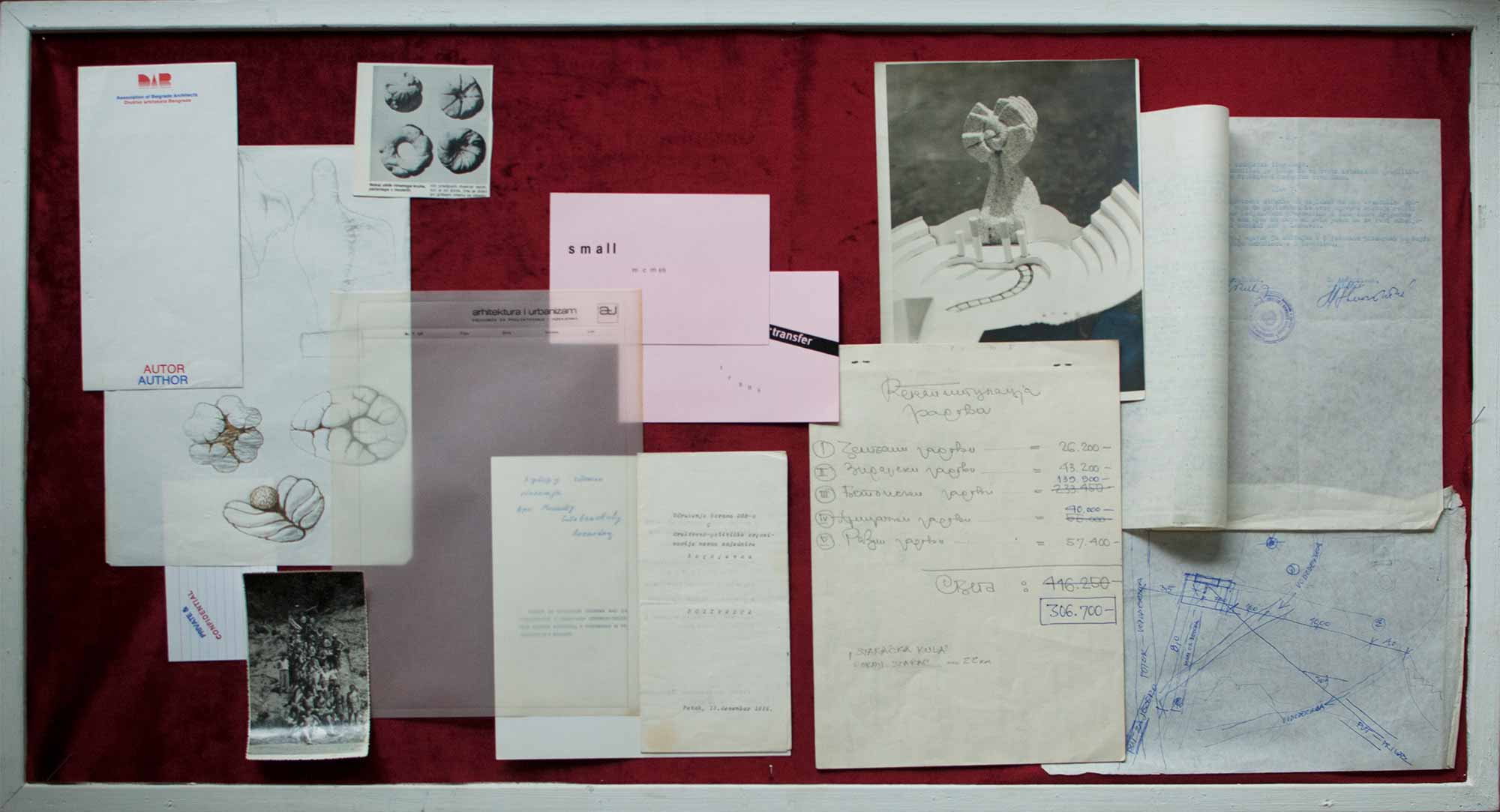

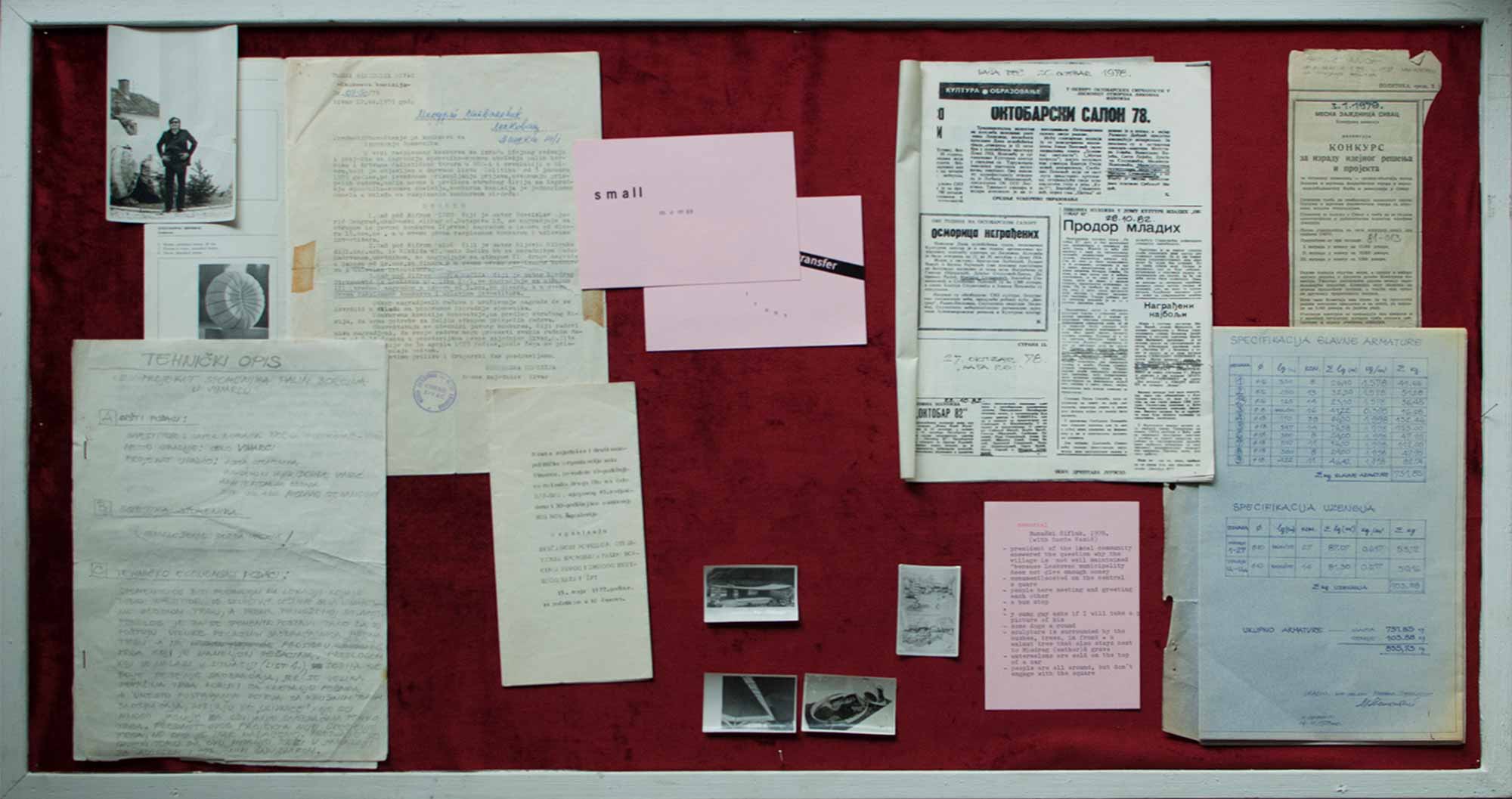

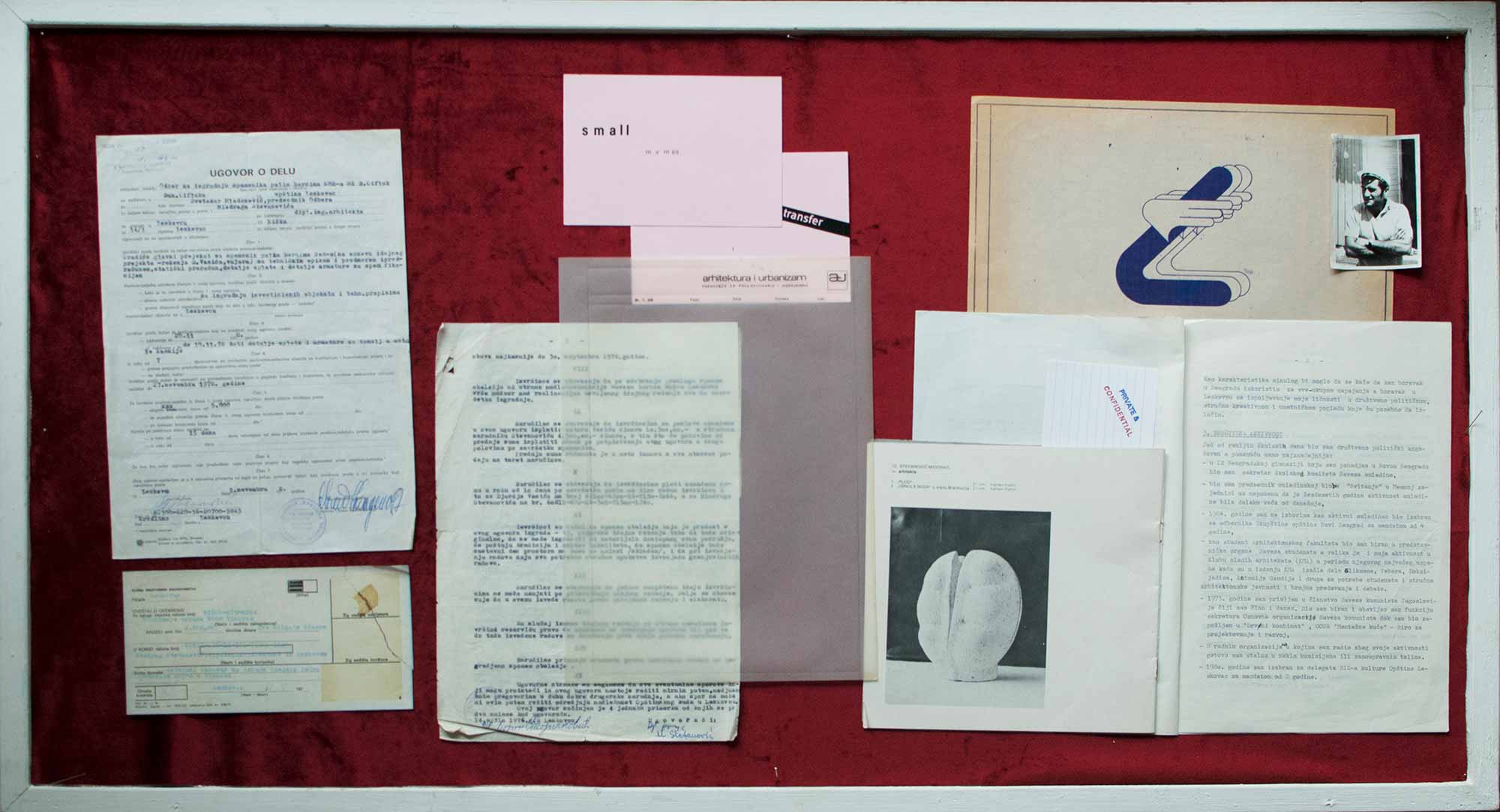

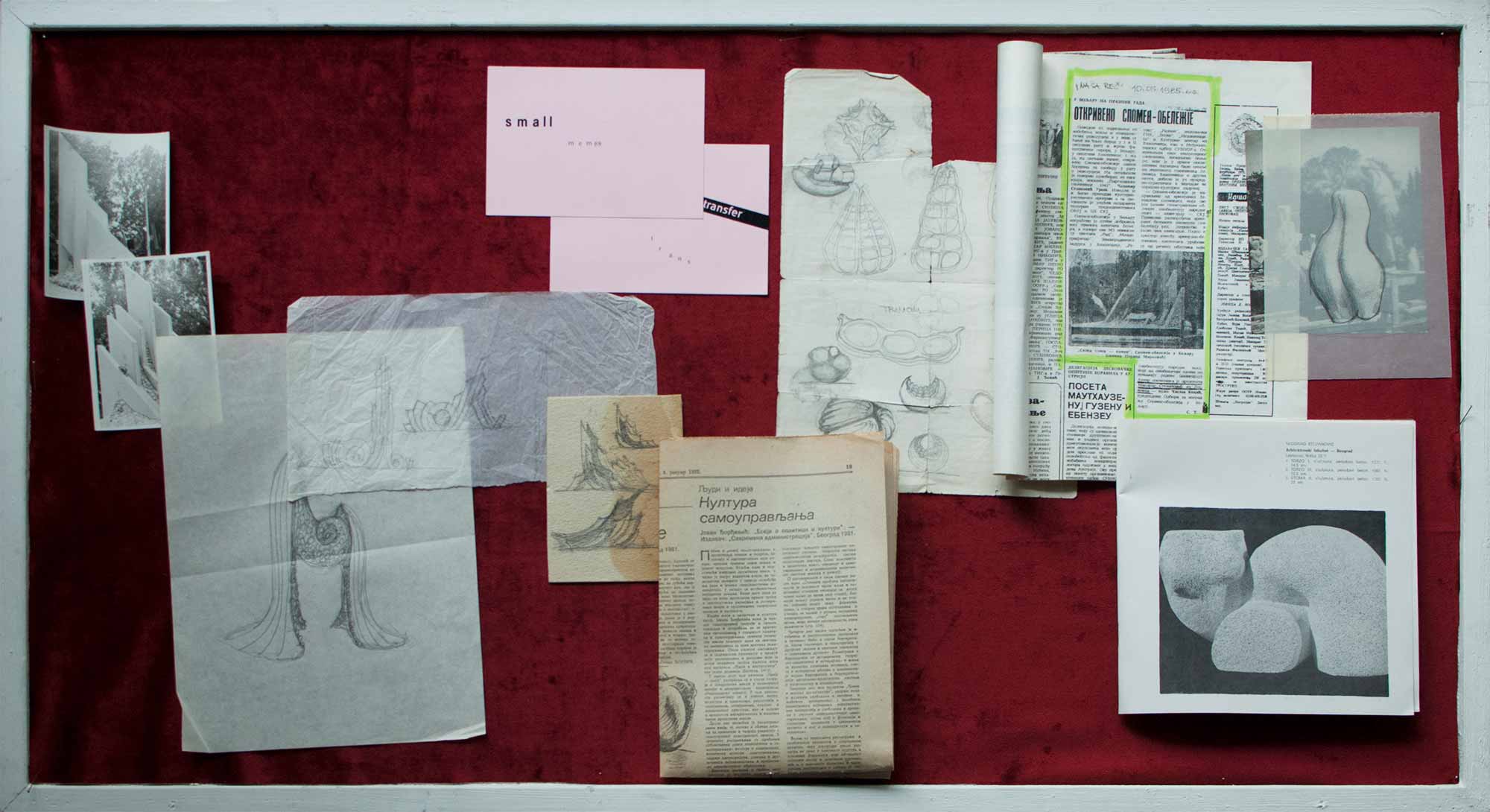

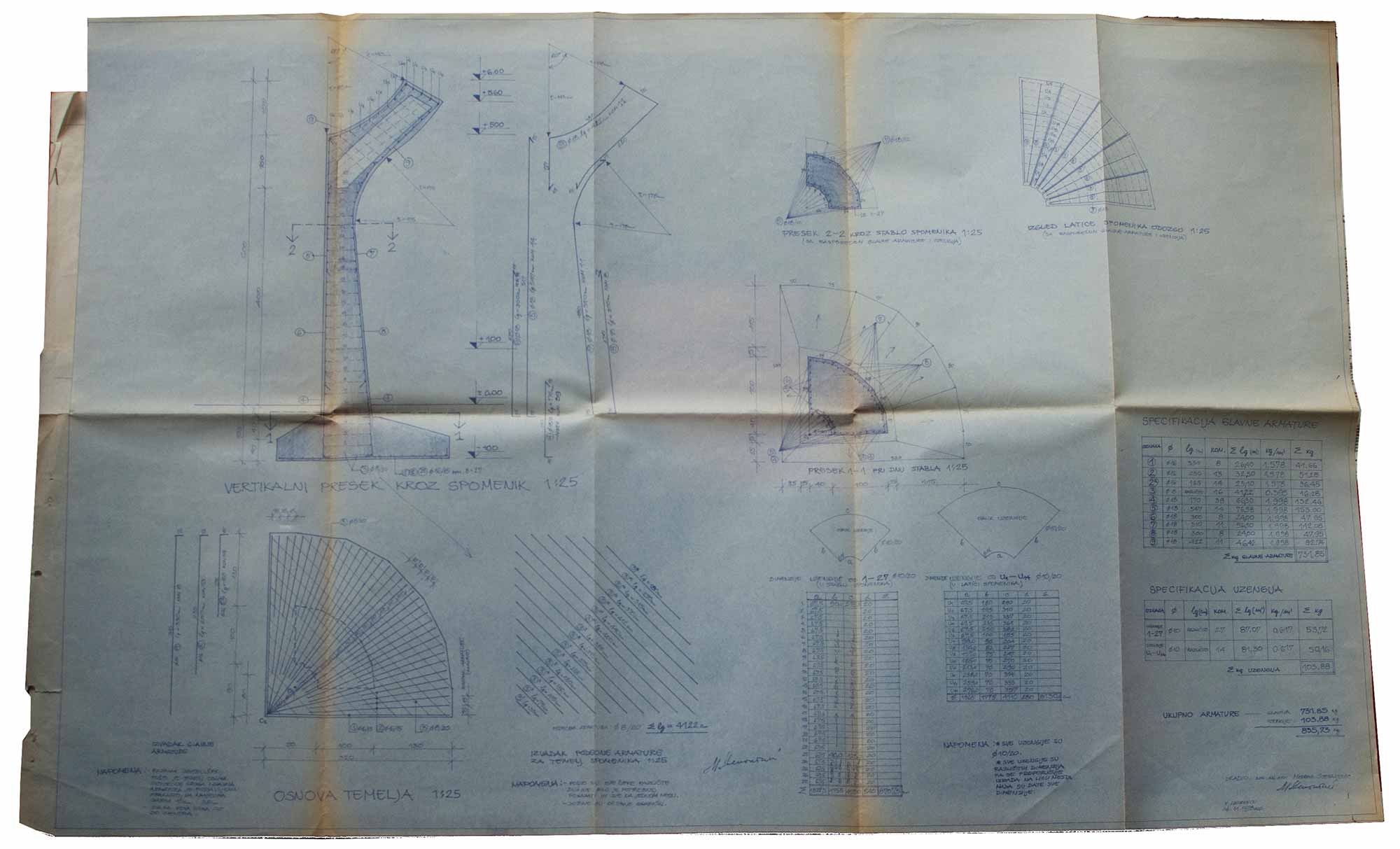

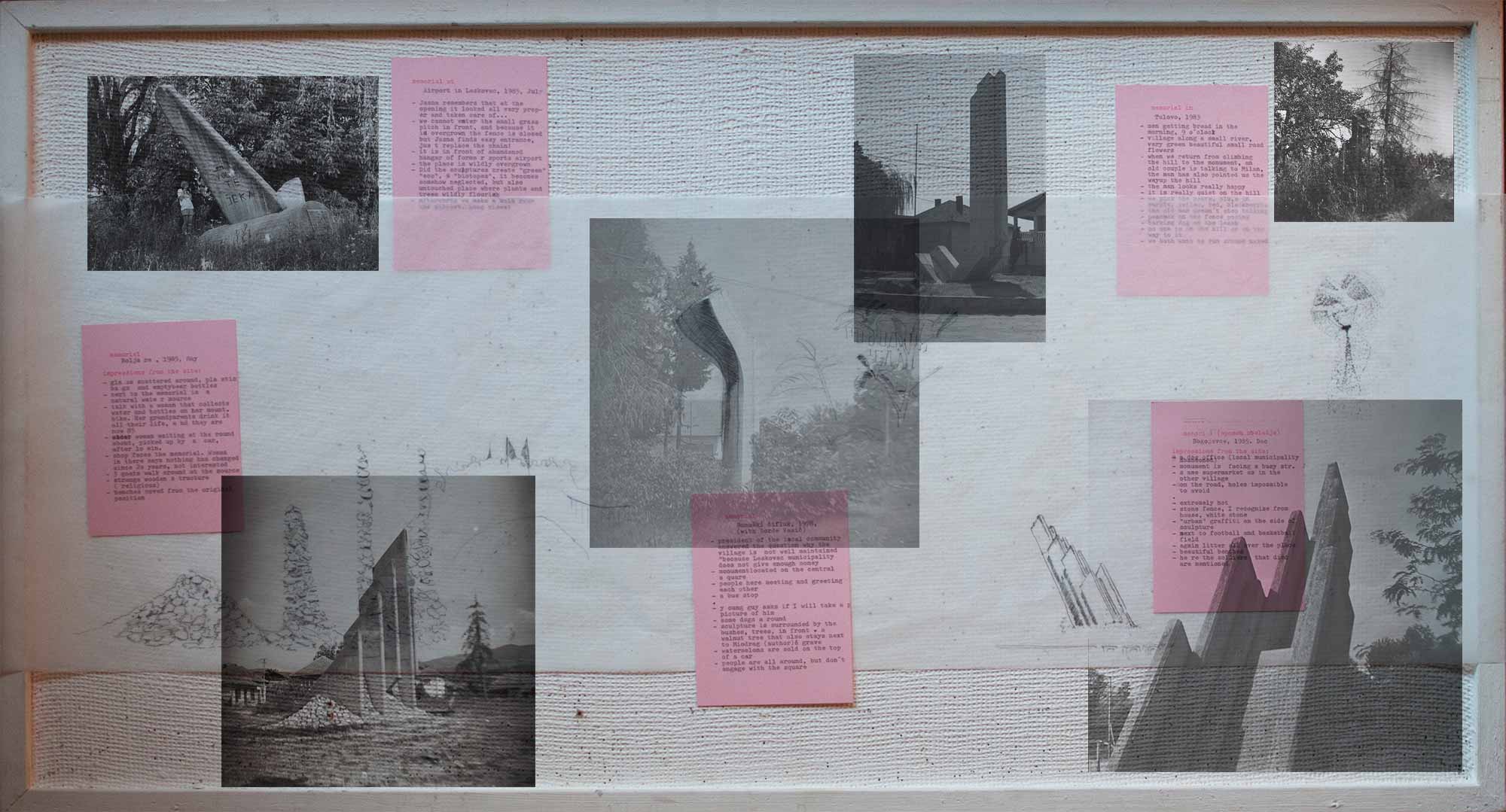

(small memorials) consists of a series of attempts to read and create referent points of translation into the presence of a ‘directly lived’ experience, however, these are not entirely past, dead, nor finished. Photographs, drawings, and contractual documents of partisan memorials designed by my father, and in collaboration with others, brought to life via family archive and my repetitive acts of mourning, are more than just private souvenirs. Marginal in scale, location, and representation compared to the world-famous, gigantic sculptural works erected in the place of famous WWII battles across Yugoslavia and today eulogised across architectural press – these forgotten, local, small memorials, situated on the outside of the heroic past, are today revisited and redocumented in their dusty present, and so become transmitters, pointing to the larger social history and class contradictions within architectural production, in the time of workers’ self-management.

Re-reading the unofficial, home archive as the site of trauma – both personal and political – alongside live encounters with the memorials’ afterlives necessitates questioning abstractions inherent in the modernist tradition: of labour, of the working class, of certain ‘structures of feeling’, as a part of practical consciousness in any social formation, and as conceptualised by Raymond Williams in his 1977 essay published in the Marxism and Literature volume, and recommended to me by Nick Beech. Williams warns that focusing solely on official consciousness, and using finite forms and fixed, objective facts is insufficient; instead, he proposes recognising that culture is produced of equally meaningful, alive, and personal feelings. The cancellation of the opposition between the objective and subjective thus sketches social experience as ‘still in process’, embryonic, and in solution. Social practices of memorialisation, not just the authority of the architect and artist, construct what I call ‘small memorials’, an elusive inheritance beyond photography’s representational limits. In a society which privileges individual agency and private property, memorials’ constitutive profanations present technical and ideological obstacles to the translation of their social meaning beyond the notion that they are mere objects of representation. The other trauma this work addresses is my personal recollection of my father’s repeated lament over the ‘missed opportunity of the working class’ in the late 1980s, foreclosing any possibility of socialism’s survival, though then still officially existing. The project aims to outline thus conjured individual and collective agencies intertwined. To translate, Susan Sontag suggests, is to ‘hand “over” or “down” (originally something material) to others’, in this she is noting the proximity of traduction (the French word for translation) to tradition. Translating the geographical and historical sites of the ‘missed opportunity’ via (small memorials) unavoidably encounters the antagonistic traditions of the architectural practice and working-class ideals. Attending to the workers self-management’s emergent notion of the self as always in formation, (small memorials) seeks to transcend the proleptic disposition of this cultural tradition.

My work is situated at the intersection of architectural history, critical theory, and cultural studies, focusing on questions of labour, technology, subjectivity, and knowledge production. My PhD thesis ‘Incorporating Self-management: Architectural Production in New Belgrade’ (Newcastle University, 2019) explored the ways in which the constitutionally established workers’ self-management in post-war Yugoslavia influenced the organisation of architectural techniques. I argue that self-management was constituted by three intertwined concerns: as a revolutionary notion, a concrete social policy engaging Yugoslav workers in governing processes, and as an everyday architectural practice in designing/constructing New Belgrade. By analysing a range of sources – technical and legal documents, educational literature, personal inheritance, oral history – the thesis’ focus on material conditions of architectural production over the four decades of socialism elucidated for the first time in detail how self-management’s contradictions significantly played out in social relations and the everyday realm of architects’ work. This research is the basis for a book project currently in preparation. Examples of my recent publications engaging with the related themes are: ’Postmodernism Unfinished: Forging the Humanist Subject in New Belgrade’ (in Architecture in Effect, 2019); ‘Overpainting that Jostles’(with Sophie Read, in Architecture and Feminisms, 2018); ‘Tools for conviviality: architects and the limits of flexibility for housing design in New Belgrade’ (in Industries of Architecture, 2016), etc.

My research practice has evolved in dialogue with interdisciplinary and art collaborations, which resulted in international exhibitions, artist’s books and residencies. Examples include the following projects: on growing exhaustion in art-production, illness, and self-care, with The Feminist Healthcare Research Group, exhibited as Sick Leave at District, Berlin, 2016, with the publication ‘Political Feelings’; on autobiographical testimony’s claim to authenticity: ‘A Partial Index’ (with Peter Merrington, artist’s book and exhibition at Baltic 39, Newcastle, 2014); on resistance and individual authorship in architecture: ‘I am too sad to dissent’ (as an artist in residence in Flutgraben, Berlin: Watchtower Schlesischer Busch , 2013). One phase of this project has been exhibited as ‘Bureau d’études’ at Newcastle University research conference, 2014.

I am currently Postdoctoral Research Fellow at The Royal Institute of Technology, KTH Architecture, Stockholm, where alongside conducting my core project ‘Normalising Flexibility: Technologies of Governmentality in Processes of Architectural Production’ I also co-teach an international PhD course ‘Approaching Research Practice in Architecture’ (hosted by TU Munich). I am also Lecturer at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, teaching architectural history and theory in MArch and BA courses. I am Affiliate Researcher to the AHRC-FAPESP project ‘Translating Ferro/Transforming Knowledges of Architecture, Design and Labour for the New Field of Production Studies [TF/TK]’, 2020-2023.

Jane Rendell’s seminal work on ‘critical spatial practice’ continues to inspire my interest in critique as engagement with public and private, entwined and co-productive. I have been fortunate to benefit from Jane’s research leadership at the UCL which facilitated invaluable feminist approaches to the specific ethical dilemmas in academic work. Although thematic focus of my research is not always explicitly feminist, building my practice in the direction of ‘feeling with(in) thinking’ has been greatly influenced and encouraged by Katie Lloyd Thomas and her feminist theory and practice of ‘building while being in it’.

Barthes, Roland. 2000. [1980]. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. by Richard Howard (London: Vintage).

Bloch, Ernst. 1986. The Principle of Hope Vol.1, trans. by Neville Plaice, Stephen Plaice, and Paul Knight (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press).

Comay, Rebecca. 2008. ‘Missed Revolutions: Translation, Transmission, Trauma’, Idealistic Studies, 38.1–2: 23–40.

Sontag, Susan. 2001. Where the Stress Falls (London: Penguin Books).

Steedman, Carolyn Kay. 1986. Landscape for a Good Woman: A Story of Two Lives (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press).