- Login

Critical Spatial Practice

Female Futures Lexicon on Space is an open collection of statements on the utopian production of (domestic) space—from a feminist position. It helps rethink the modern production of space, its history and future, its authors, inhabitants, and its discourses—in a moment of political and social regression.

The installation and text explore currents of thought and practice—from 1918 to 2018 by way of 1968—that have produced alternative futures through a feminist perspective: architectural projections and speculations, utopian ideas and visions that react to the ideological implications and effects of Modernism.

In terms of structure, the lexicon is an open and growing archive that can go from a word to a phrase, from a drawing to a floor plan, from a video to a model, from an argument to an entire text. It has the power to say, the power to do, as well as the power to undo, to counter, to contradict, and especially the phantasmatic power to bring about (Derrida, originally published in French in 1993, “On the Name” 1995).

One entry of the lexicon for instance reads:

Jinwar Free Women’s Village (Kurdish women’s movement, since 2017)

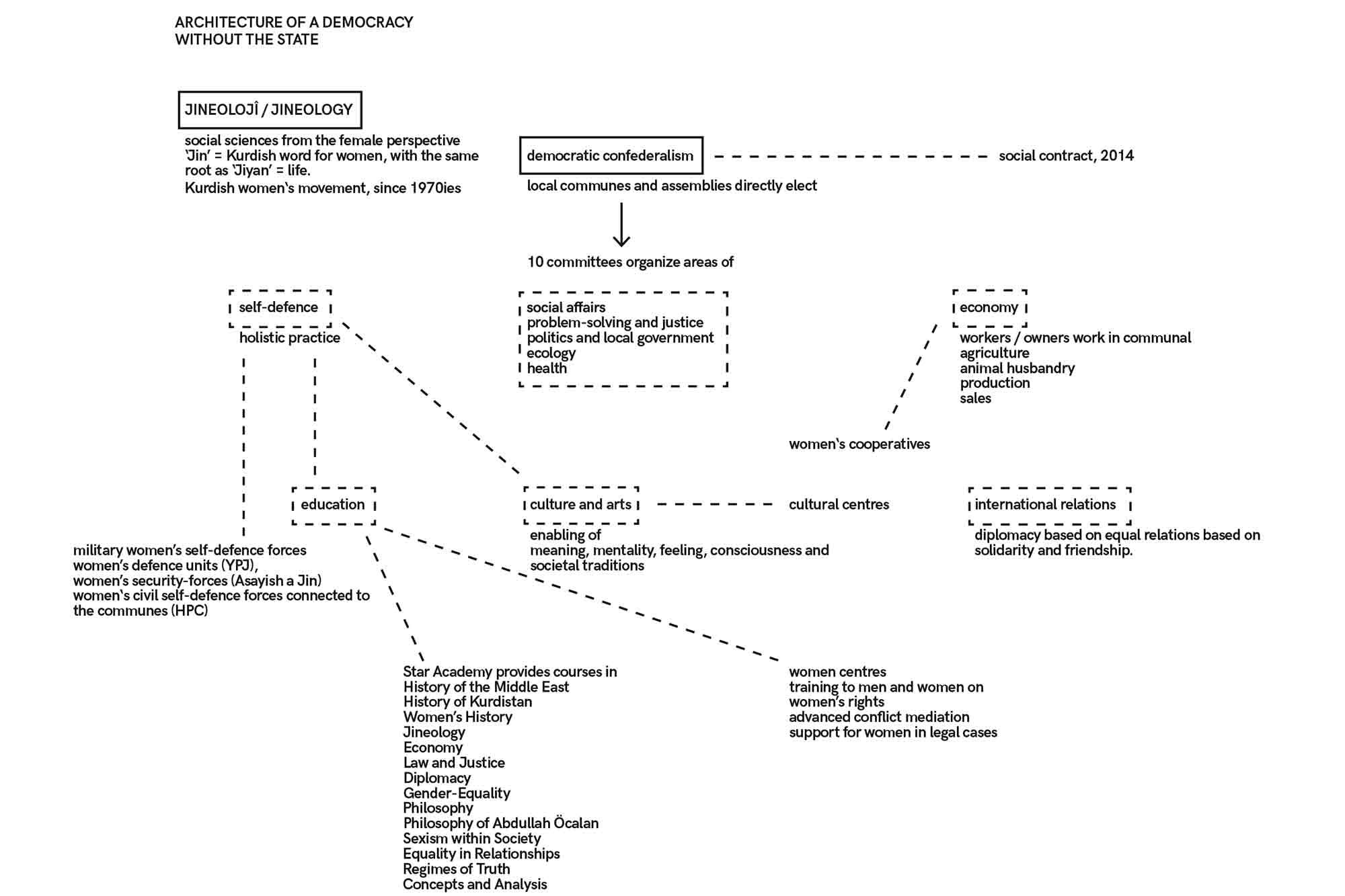

Free communal settlement, bound to Jineoloji, the science of women and free life. The ecological village is currently under construction in the center of Rojava (western Kurdistan / northern Syria).

Jineoloji goes back to Abdullah Öcalan and his reading of Murray Bookchin and develops a theory along three basic principles: democracy, ecology, and women’s liberation. As a new science, it criticizes the modern connection between male hegemony, oppression, and science and aims at reinterpreting mythology, religion, philosophy, and science. As an anti-modernist political ideology, it advocates “democracy without the state,” an ideal based on local self-governance, gender equality, communal economy, and cultural and religious diversity.

In the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria, Jineoloji has become an official part of the education system, being taught in schools and at Rojava University.

Based in Berlin, Asli Serbest and Mona Mahall have been working as a collective since 2007. In their research-based practice they reflect and produce space through various media: architectures, exhibitions, installations, scenographies, as well as (video-)texts, concepts, and publications. Their projects are explorations of particular past, present and future contexts and aim at negotiating the evolving relationship between architecture, art, and the political.

They exhibit and publish internationally, among others at Biennale di Venezia, 2012, 2014, 2019; Württembergische Kunstverein Stuttgart, 2015, 2018; Riverrun Istanbul, 2018; Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, 2017; Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York, 2014, 2015; HKW, Berlin, 2012; Vancouver Art Gallery, 2013; Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, 2013; New Museum, New York, 2009; in e-flux journal, Volume Magazine, Perspecta, The Gradient–Walker Art Center, Istanbul Art News, AArchitecture, Deutschlandfunk, etc.

They were the curators of the 7th International Sinop Biennial 2019.

They are the authors of a book on the speculative character of modern architecture (How Architecture Learned to Speculate, 2009) and the editors of Junk Jet, an independent magazine on architecture, art, and media. They have taught as professors of Foundations of Design and Experimental Architecture at the Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design, as professors of Architecture at Cornell University and of Spatial Dynamics at Rhode Island School of Design.

In the process of archiving, of building up a lexicon or a canon, we have to address the limits of any classificatory or selective operation as conventional and exclusive. We refer to Jorge Luis Borges to develop the logic by which we try to (self-)critically choose projects, things, or events. In his renowned essay on The Analytical Language of John Wilkins he introduces a system of classification that:

“doctor Franz Kuhn attributes to a certain Chinese encyclopaedia entitled ‘Celestial Empire of benevolent Knowledge’. In its remote pages it is written that the animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.”

[Jorge Luis Borges: The Analytical Language of John Wilkins, in: ‘Other inquisitions 1937-1952’ (University of Texas Press, 1993)]

The Situationist International (1957-1972) edited by Stefan Zweifel et. al., 2007.

Dolores Hayden, The Grand Domestic Revolution: A History of Feminist Designs for American Homes, Neighborhoods, and Cities, 1981.

Jorge Luis Borges, The Analytical Language of John Wilkins, 1952.