- Login

Critical Spatial Practice

‘Our spacecraft, Cyclops 1, will soar into deep abyssimal [sic] space beyond the epicycles of the seventh heaven. Our posterity, the Black Scientists, will continue to explore the celestial infinity until we control the whole of outer space.’

“Dr.” Nkoloso, ‘The Moon and I’, Abercornucopia, 10 January 1964.

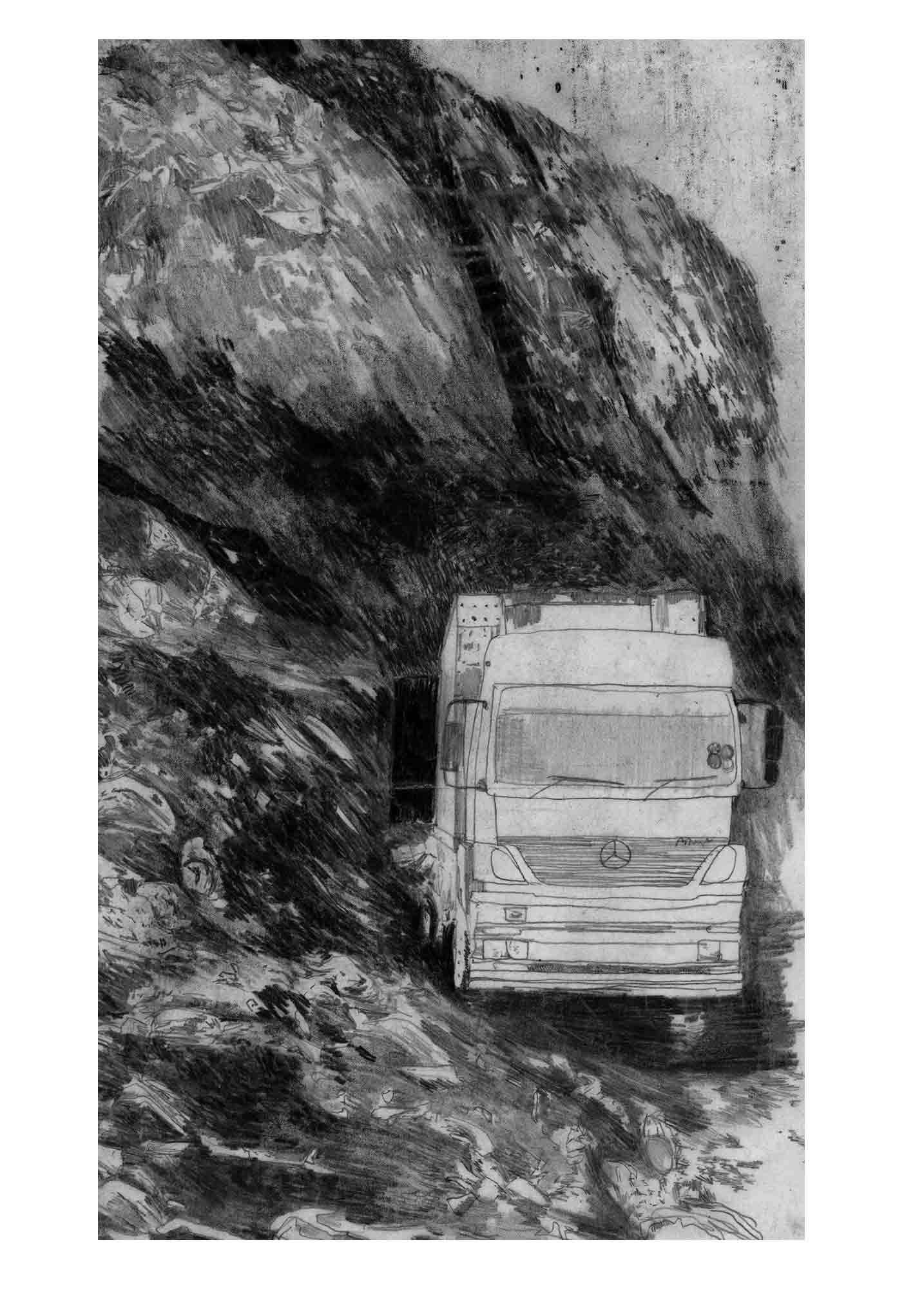

On 24 October 1964, thousands of people gathered in Lusaka to celebrate Zambia’s Independence. Had funding constraints not curtailed their ambitions, the day might also have seen the launch of Cyclops 1, the spacecraft of the Zambian Space Program. Western media outlets regarded the painted metal barrel with its single porthole as a laughing matter, her crew, ‘a bunch of lunatics’.

More attentive readings suggest that the Space Program in Lusaka’s ‘Chunga valley’, led by freedom fighter Edward Festus Mukuka Nkoloso, offered significantly more than the goal of simply bursting from the atmosphere. Instead, bound together with the very idea that a Zambian could go to the Moon (then on to Mars), and the seriousness such an objective demanded of its participants, was the requirement that one reconceive of the possibilities available to African bodies, right here on the ground.

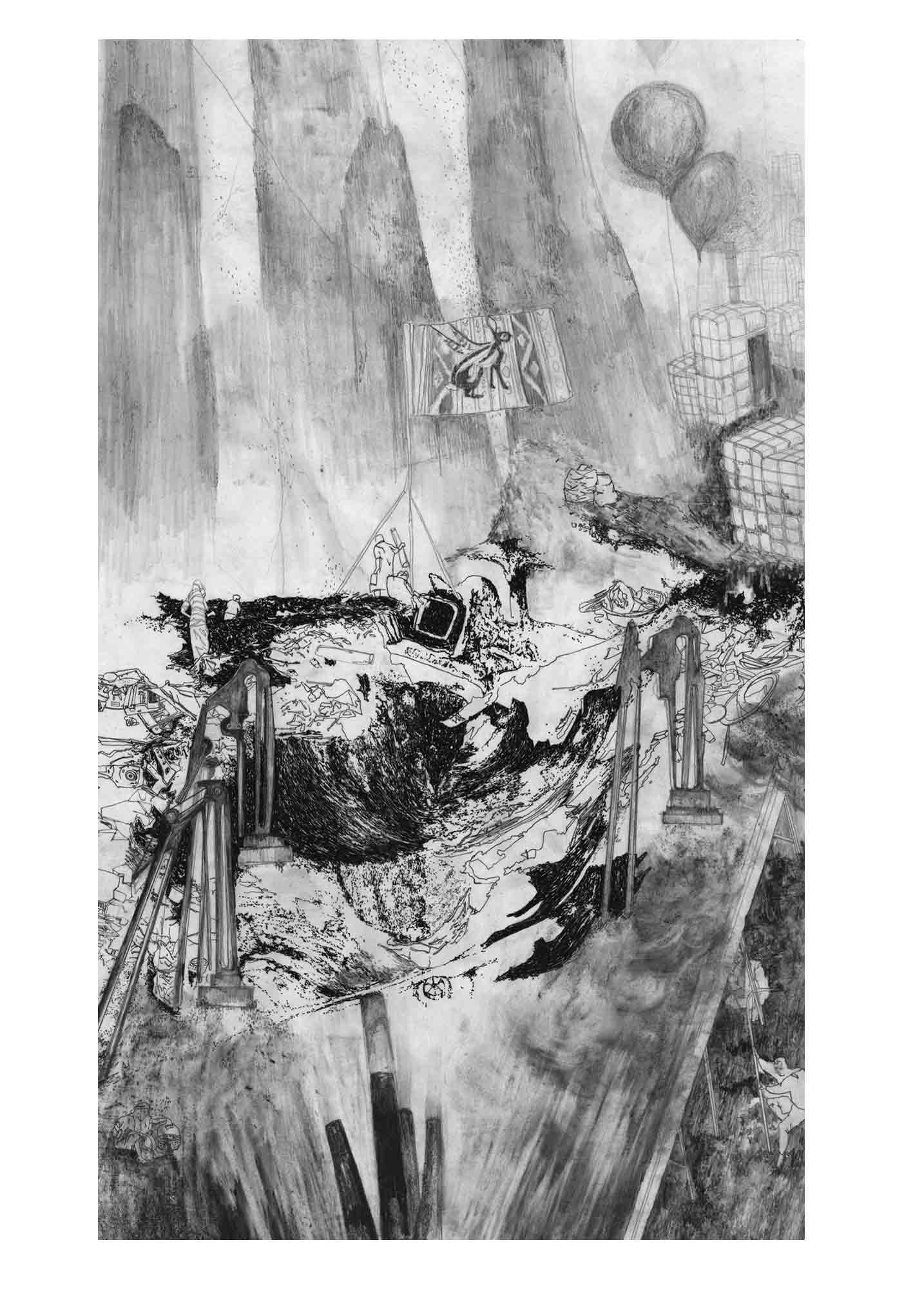

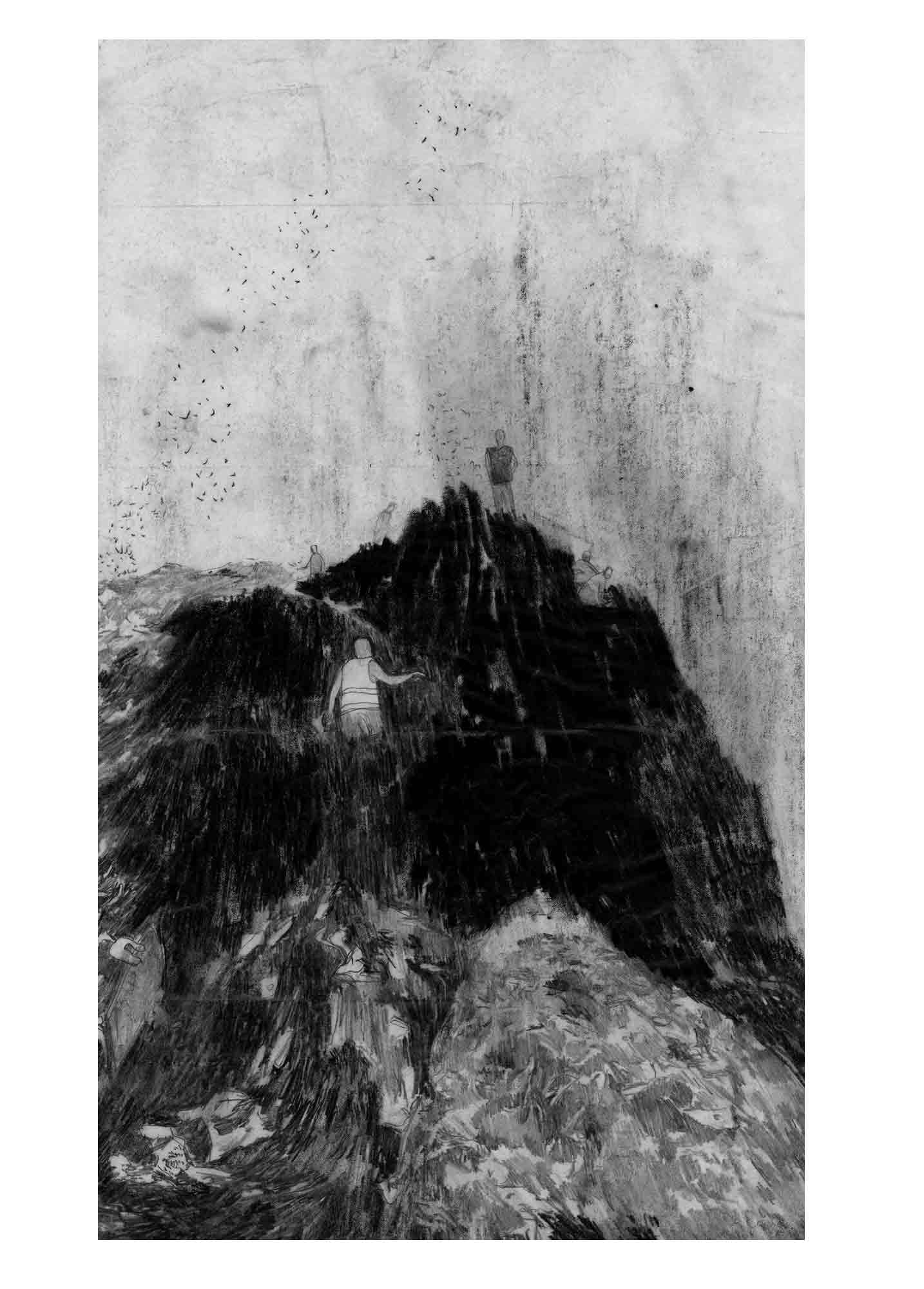

Nearly 55 years later, with the Chunga Landfill facing the threat of privatisation and with this, the potential expulsion of over 300 Waste Recyclers, we set out to revive Nkoloso’s practices on the site. Bringing together representatives from the Lusaka City Council and the Chunga Waste Recycler’s Association, we cast ourselves into a new city, a terrain where the rules of engagement were remade.

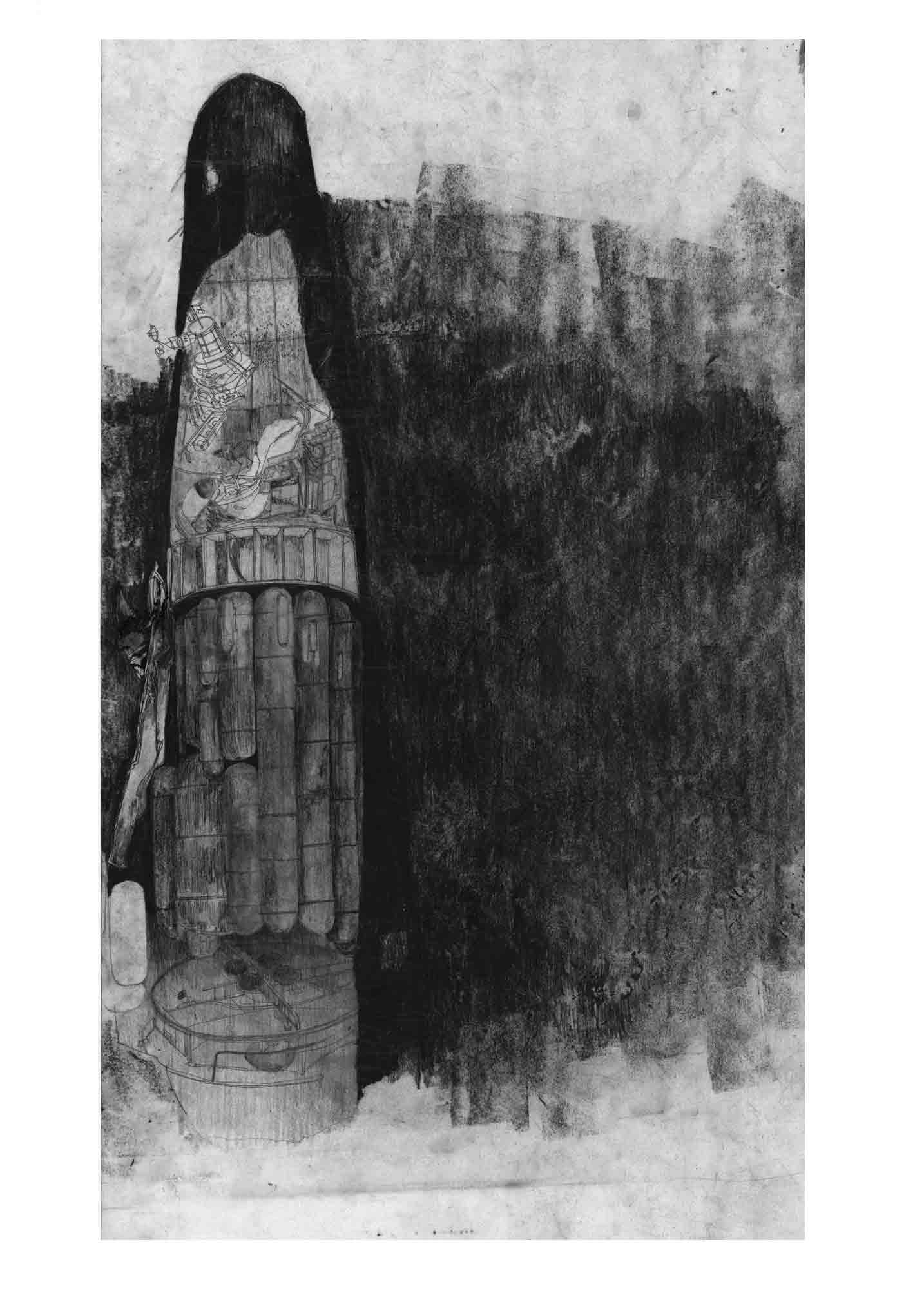

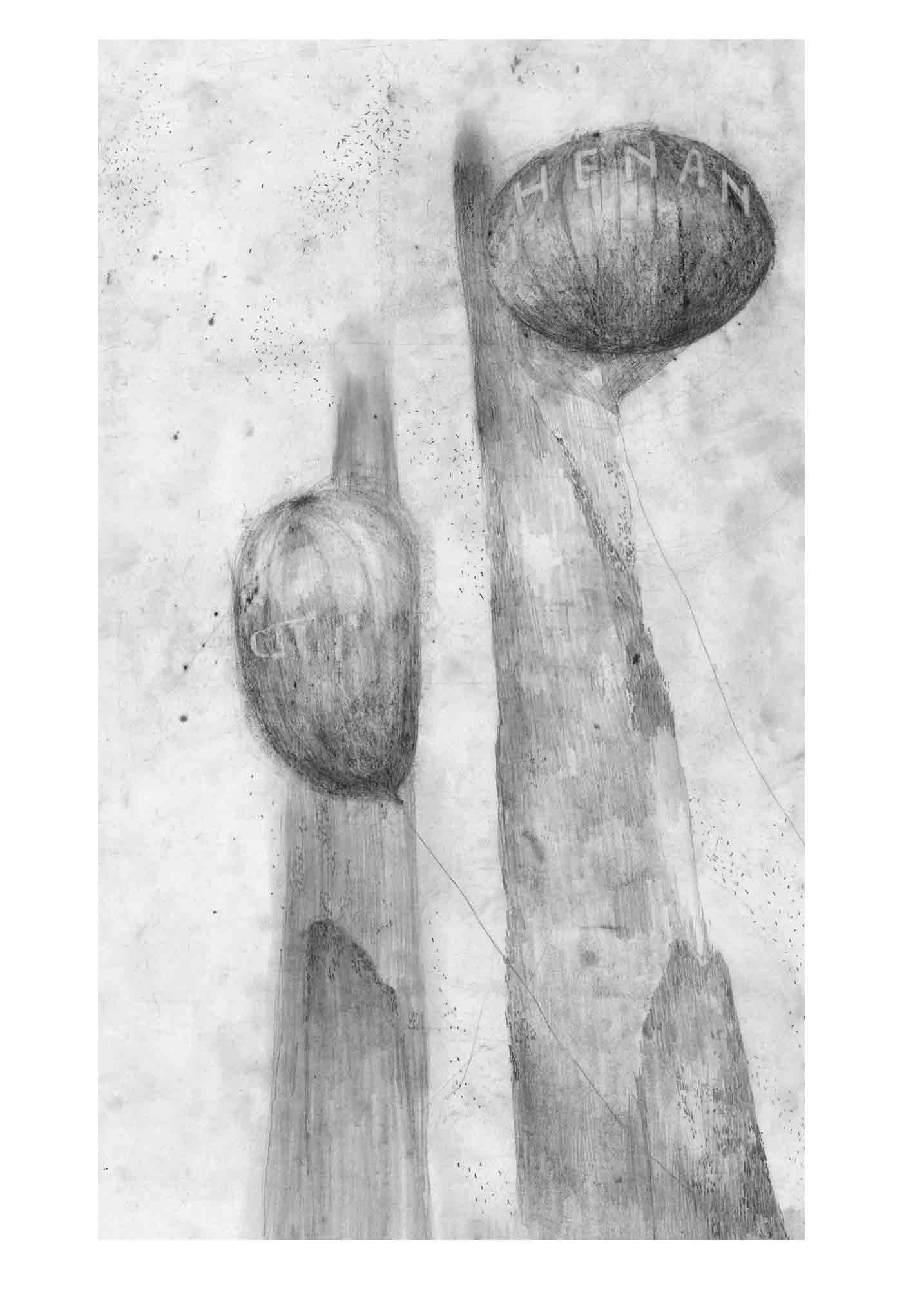

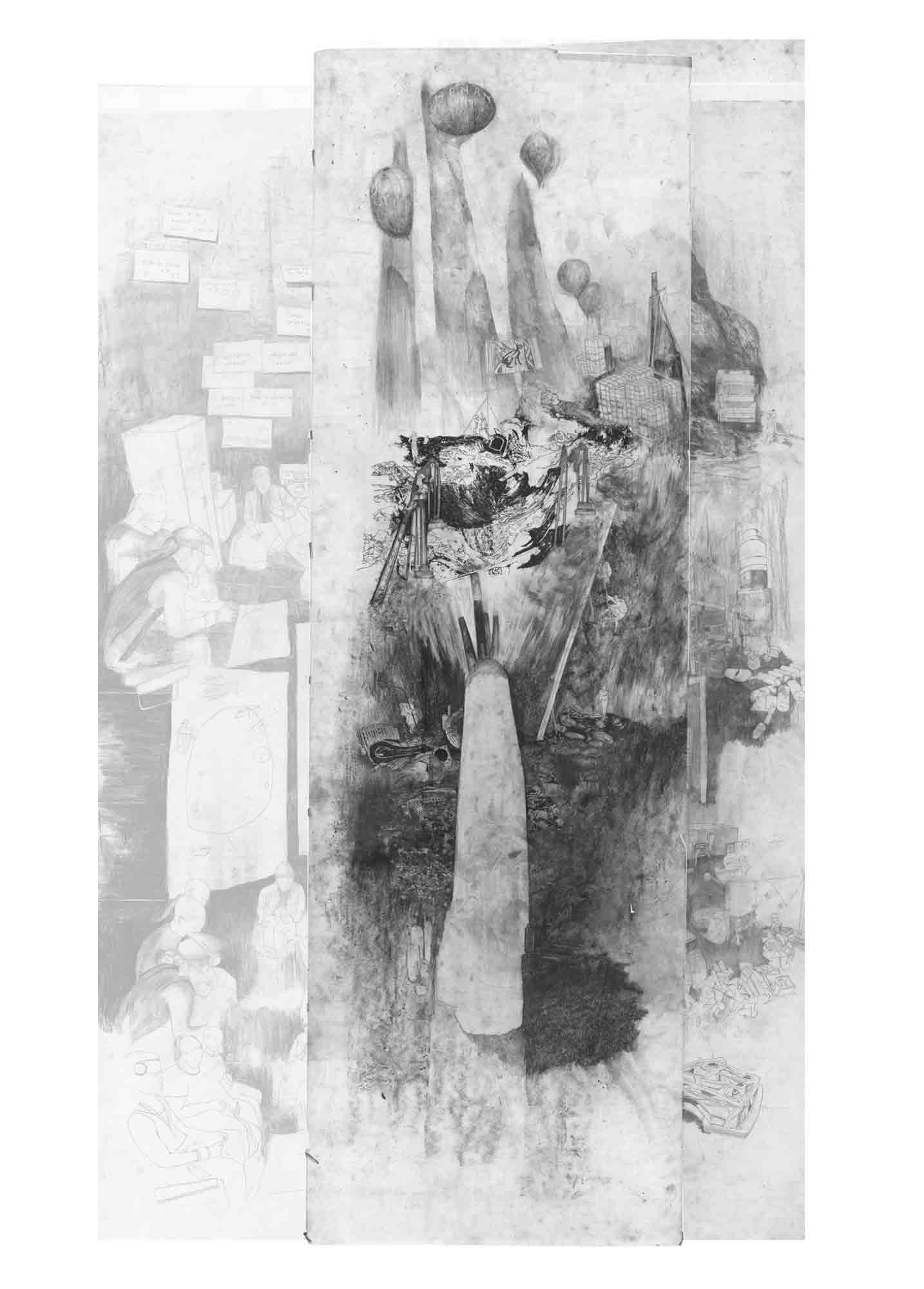

In the fictional city of Mailo, an earthquake has occurred revealing an unexploded spacecraft that has lain dormant for decades. Mailo is a weird city; drawing on the real-world model of Lusaka -yesterday, today and tomorrow – infused with elements of science fiction and fantasy. Mailo is familiar and, simultaneously, modabwitsa chachilendo, amazingly strange. Looking at, and through, the drawings of Mailo, landscapes, characters and practices from Lusaka can be seen. They are recycled, distorted and, in the process, remade. The weirdness of Mailo attracted much interest. This was not your typical consultation, and yet it has prompted many ideas for how a collaboration between City Council and Association can be forged, towards an alternative to the privatisation of the site. From a weird city, weird practices towards a weird-tender.

Thandi is an architectural designer-researcher who operates through design, fiction and performance to interrogate our perceived and lived realms and to speculate on the possible worlds in our midst. Using fictions as design tools and tactics, she engages in projects which provoke questions, whilst working with communities and policy makers towards acting on those provocations. Thandi is currently a PhD candidate at The Bartlett supervised by Jane Rendell, CJ Lim and Camillo Boano. A long-time admirer from afar, Thandi was introduced to Critical Spatial Practice and Site Writing, in earnest, in the first year of her PhD when, between trips to Lusaka, she took part in the Theorising Practices/Practicing Theory module in the MA Architectural History at The Bartlett, led by Jane Rendell. Central to Thandi’s research is a live project, investigating how insertions of the other worldly and the downright weird can support the Lusaka City Council and the Chunga Waste Recycler’s Association produce a speculative ‘weird-tender’ recognizing the community as partners of the state; offering a counter to extractive urban agendas & influencing the future of the city dump. Thandi is a Roving Hybrid Tutor at the Graduate School of Architecture (GSA), at the University of Johannesburg. At the GSA, she is affiliated with Unit 12, a unit led by Sumayya Vally, that is committed to developing an African almanac of contemporary architectural speculation.

In describing critical spatial practice, Jane Rendell writes of ‘works [that] can be positioned in ways that make it possible to question the terms of engagement of the projects themselves.’ (1) My approach has sought to explore the critical, productive potential of such ambiguity. Revelling in the space of the weird, where everyday landscapes, practices and characters are recognisable, and yet amazingly strange, and through similarly unstable mediums – such as drawings that are developed and altered through people’s interaction with them, or props which demand interpretation to be put to use – such that space is opened for hierarchies to be reconfigured, and for excluded groups to be brought to the fore.

A question I have been asking is what it means to situate ‘critical spatial practice’ itself, a concept developed in the United Kingdom, in relation to work in Zambia. In articulating ‘critical spatial practice’, Rendell points to her extension of the term ‘critical theory’ to include later theorists – among them the post-colonial – that she identifies seek to ‘transform rather than describe’ contexts towards social change. (2) Through ‘critical spatial practice’, Rendell further extends ‘critical theory’ to include the ‘critical practices’ through which these transformations might occur. (3) I think there are clues in this project, which speaks to acts of disrupting hierarchies of power and knowledge, and relations between bodies, bodies and matter, and bodies and the Earth, that are rooted in colonialism. Perhaps, as my and would-be-astronaut Nkoloso’s work suggests, a critical spatial practice which builds, and builds on, decolonial ambitions seeks to make transformations in these realms and relations. I look forward to continuing to think through the way a concept such as this travels – geographically, politically and, as a resulting, epistemically – and the work it does, and is done to its original context, in the process.

(1) Jane Rendell, ‘Critical Spatial Practice’, Art Incorporated, Kunstmuseet Koge Skitsesamling, Denmark (2008). http://www.janerendell.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/critical-spatial-practice.pdf, 2

(2) Ibid., 3

(3) Ibid., 3

Chimurenga, Chimurenga Chronic and the Pan African Space Station: https://chimurengachronic.co.za, https://www.theshowroom.org/exhibitions/the-chimurenga-library (8 October – 21 November 2015, London)

Baloji, Peau de Chagrin / Bleu de Nuit (With Subtitles) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TzHM_JLgqO0 , 22 March 2018, Democratic Republic of Congo/Belgium

We Intend to Cause Havoc, Zamrock band, 1970s, Zambia, works re-released by Now Again Records, 15 April 2012, USA https://www.nowagainrecords.com/witch-we-intend-to-cause-havoc/, https://www.youtube.com/watch?list=PLKijeAOQYrq21oc5DE5nYsy8D_J_Cw4hi&v=_qFO1yVUj_o