- Login

Critical Spatial Practice

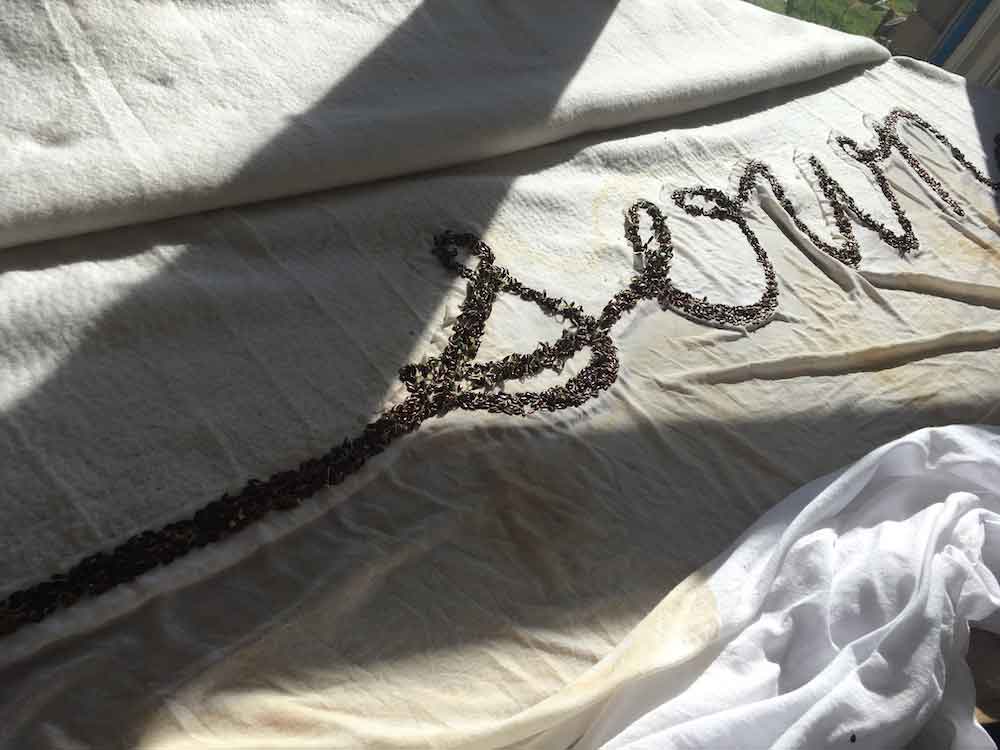

In this series I ask ’what happens when words become material? Ecological? Unstable? Can we sever concepts from the continents of abstract thought that precede us?’ I have tossed words into familiar environments – my paddock, kitchen, and backyard – inviting other critters – yoghurt, bacteria, dirt, introduced grasses, ancient seeds, sun, fire, rain, time – to collaborate with me.

Gregory Bateson, zoologist, linguist, cybernetician, and philosopher, argued in 1972 that until we change the ‘ecology of our minds’ we will be unable to restore the living ecologies of the planet. His argument goes like this: academia perpetuates wrong-thinking by its traditions of working with abstract text. By always positioning new work within a continuum of thought, dislocated from the specificity of place, the academy promotes the idea that environments are subject to our manipulation. Academia’s chief role is to ‘disseminate’ knowledge, a concept that has its roots in the Latin ‘disseminare’, meaning to scatter seeds for propagation. The word carries with it a presumption that ecologies are something that humans manipulate, indeed, it is virtuous to manipulate them. In fact, ecologies reproduce quite well without human intervention. Text-isles: sowing an idea, is a different kind of dissemination. Erase is a critical spatial practice in my front paddock in the Otways in spring. Culture takes place between the dairy next door, its milk and the cultures that grow in it, and my clothes line. Sown is a collaboration between linseed and some cotton in my kitchen. Over a period of three weeks the seeds germinated on the muslin and the roots ‘stitched’ a seam through the cotton wadding beneath.

Janet McGaw is a Senior Lecturer in Architectural Design in the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne. She is a qualified architect and has a PhD by Creative Works from the University of Melbourne. Her research, teaching and creative practice for the past two decades has been motivated and inspired by the critical turn in architecture that took place in the latter part of the 20th century. Transdisciplinary encounters with philosophy, feminist theory, anthropology, geography, Indigenous ways of knowing and being, and political ecology have all been important lenses through which to critically reflect on architectural discourse and practice. Janet uses methods that are discursive, collaborative and sometimes ephemeral. Urban Threads (2008) her PhD by creative works, involved a collaboration with women who had experienced homelessness and isolation. Together they asked how people without land, money and power can shape the urban fabric. Janet teaches architectural design, coordinating the undergraduate pathway in architecture, the final subject of the Masters degree, Design Thesis, and a Masters elective, Design Research. She has published widely in journals and scholarly books and is currently enjoying doing some material thinking with more-than-human collaborators.

Art and Architecture: A Place Between was published as I was completing my PhD and was a light-bulb moment. Jane Rendell’s definition of ‘critical spatial practices’ as creative practices in public space that are more contingent and socially engaged than public art, but less concerned with pragmatics, enabled me to theorise the way I had been working. It has been important for my teaching and creative work ever since.

CA Bowers, ‘Gregory Bateson’s Contribution to Understanding the Linguistic Roots of the Ecological Crisis’ The Trumpeter, v. 28., n. 1., (2012) pp 8-42.

Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene’ (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2016)

Edyta Supiñska-Polit, ‘Seed and Growth: The Art of Teresa Murak’ in Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka (ed.), The Creative Matrix of the Origins: Dynamisms, Forces and The Shaping of Life, (Berlin: Springer, 2002)